Situatie

Solutie

Installing software should be simple and convenient. How simple and how convenient that turns out to be is largely down to the package manager of your distribution. Package managers are software applications that let you download other Linux programs, and install them.

Derivative Linux distributions tend to use the package managers of their parent distribution. For example, the many Debian variants and derivatives use

apt, the RedHat and Fedora distributions use

dnf, and the Arch family of distributions use

pacman. So, thankfully, there are not as many package managers are there are distributions.

Even so, from a developer’s point of view, supporting all the different package formats means wrapping your application into a DEB file for the Debian family, into an RPM for the RedHat family, and so on. That’s a lot of additional overhead.

It also means that if neither the developers nor anyone else has created an installation package for your distribution, you can’t install that software. At least, not natively.

You might be able to shoehorn a package from a different distribution onto your computer, but that’s not a risk-free method nor is it guaranteed to work. If you know what you’re doing you can download the source code and build the application on your computer, but that’s a far cry from being simple and convenient.

Projects such as Snap and Flatpak were designed to overcome the problem of wrapping applications for each distribution. If you can wrap a package into a single file so that it comes bundled with the appropriate libraries and any other dependencies it has, so that it makes (virtually) no demands on the host operating system, it ought to be able to run on any distribution.

The AppImage project is just such an initiative. AppImage is the name of the project, and AppImages are the name for the wrapped applications.

How AppImages Work

AppImage files are not installed in the traditional sense. The component files that make up the application package are all contained inside a single file. They are not unpacked and stored in different directories in the file system.

An application installed by your package manager will have its executable copied into the appropriate “/bin” directory, its

manpages will be stored in the “/usr/share/man” directory, and so on. That unpacking and copying step doesn’t happen with AppImages.

There’s a file system inside an AppImage, usually a squashFS file system. The files needed to run the application are stored inside this file system, not in the main file system of your Linux installation. When the AppImage is executed, it launches one of its internal helper programs that mounts the squashFS file system in “/tmp/mount” so that it is accessible from your main file system. It then launches the application itself.

This is why launching applications from Snaps, Flatpaks, and AppImages is slightly slower than running a regular application. For all of this to work, the host file system must have something called “filesystem in userspace” installed. This is the only dependency AppImages places on the host. FUSE is usually pre-installed on modern Linux distributions.

Using an AppImage file

The first thing you need to do is download the AppImage for the application you want. These won’t be in your distribution’s repository. Usually, you find them on the website for the application itself.

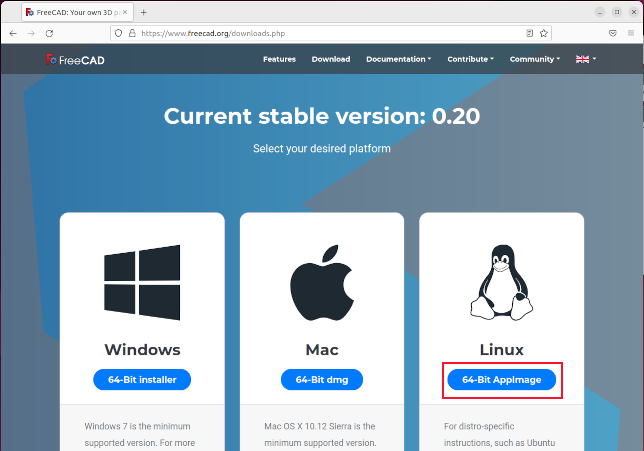

We’ll download and use FreeCAD, an open-source 3D computer-aided design package. Browse to the FreeCAD download page and click the “64-bit AppImage” button.

Leave A Comment?